A Return to Solitude- A Belfast Football Story

First published in issue 160 of the TRUE FAITH fanzine this piece by Scott Robson is a brilliant read for those interested in the intersection of football, history and politics.

The Newcastle United v Sunderland games back in 1996/97 with no visiting supporters were rubbish.

For every team you love, you have to have your hate and the and for those derby games just didn’t feel right.

Picture this scene then. Imagine if the powers that be had decided we had misbehaved so much in that fixture that they ruled we would have to play all of our games against Sunderland on Wearside.

Not as a one-off season but for three decades, almost thirty years. It is beyond comprehension.

But in Northern Ireland and for Cliftonville that’s exactly what happened for their Belfast derbies with Linfield FC.

Northern Ireland politics remains way above a Newcastle United / Sunderland rivalry as those of us who grew up at the time of The Troubles will attest.

In 1972, 479 people were killed in the province , 4,876 were injured. This was the bloodiest year of The Troubles.

Rioting on the streets of Belfast was common-place and people were frequently burnt out of their homes as sectarian mobs bid to cleanse those of the wrong religion from their neighbourhoods.

At this time football seemed a sideshow . The Irish League consisted of 12 teams of various backgrounds and preferences. This still included Derry City who would last one more year before electing to join the League of Ireland and bring successful football to the Brandywell in the nationalist area of the Bogside.

Unfortunately, football became a forum in which sectarian tensions became manifest and reflect the deeply divided society in which games were played. Though it can be argued that was ever thus and some reading this with an interest in football in Northern Ireland might have read the history of Belfast Celtic whose history provided a case in point of sectarian strife impinging upon the game in the six counties.

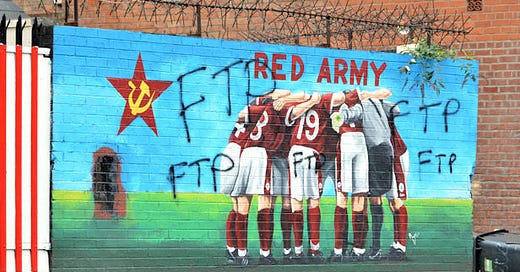

Cliftonville FC has a predominantly Catholic or Nationalist following who play home games at Solitude in North Belfast, near Ardoyne.

Linfield FC, the most successful club in the history of the game in Northern Ireland is traditionally followed by those at least sympathetic to the loyalist cause and thus Protestant in character. Linfield has a famous friendship with Rangers in Glasgow.

Cliftonville was not actually playing the day when problems came to a head. The 1970 Irish cup final was played at Solitude, between Ballymena and Linfield.

Linfield fans were attacked in the streets of North Belfast (Ardoyne) before and after the game which was perhaps predictable with the benefit of hindsight.

Local Nationalists who had saw Protestants become a minority in the area, used the cup final to increase hostility for those they had decided didn’t belong in their community. Doubtless this formed part of the tit-for-tat sectarianism which came to disfigure life in Northern Ireland.

Unfathomably, the Cup Final had been delayed until a 4pm KO to accommodate the Grand National which allowed for more time for drinking with the obvious consequences in a tinderbox situation.

Violent score settling accompanied every game and this especially applied when. Catholic Cliftonville played Protestant Portadown. Inter-community violence involving Derry City and Linfield was common place and so the RUC took the step of making Solitude a no-go zone for matches involving Linfield. Thus all games involving Cliftonville and Linfield were required to be played at the latter’s home ground of Windsor Park.

Clearly, that didn’t go down well with Cliftonville who accused the authorities of bias and providing Linfield with an in-built advantage of additional home games

Given the ruptures to life in Northern Ireland we might consider this to be a minor issue of concern but to the Nationalists of Northern Ireland and especially Cliftonville’s fans, this was symptomatic of the discrimination they faced in wider society.

Cliftonville players, officials and fans had to get used to being shepherded in and out of Windsor Park as Linfield collected 14 of their 55 Championships were won over that period.

For all of that, Cliftonville could never claim to be Linfield’s biggest rivals in challenging for trophies, that honour lay with Glentoran, another club with a largely Protestant-Unionist-Loyalist following.

But this fixture was never really about the football and the main action centred on what was happening off the pitch.

In 1998, 71 percent of people voted in favour of support for the Good Friday agreement. The peace process was signed on April 10 1998 and agreed by Dublin and London governments.

The toll of the troubles read: 3,500 dead, amongst which were 32% of the security services and 16% paramilitary groups. The remaining were civilians.

Following the Good Friday Agreement and a growing peace, sectarian divisions between the clubs began to break down. Cliftonville had a growing non-Nationalist support and Linfield had signed a Roman Catholic player around that time.

Anyone who can remember Maurice Johnston signing for Rangers and the ensuing chaos that caused in Glasgow could see how much of a leap that was in Belfast.

Thirty years after the Solitude embargo being enforced, change was in the air and after IFA President Jim Boyce referred to a “change of attitudes”, Linfield’s return to Solitude could be planned.

The RUC who had been instrumental in introducing the Solitude ban may not have been wholly convinced of the wisdom of lifting the ban but nevertheless worked with the IFA and clubs to make it happen.

For Linfield’s return to Solitude, a perhaps wiser 11am KO was agreed with the capacity capped at 1500. Linfield were provided with a 500 allocation for their supporters and subject to a heavily policed match with Blues fans bussed in and out of the game in a heavily controlled environment.

However, the underlying tensions around the game were not helped by news that Donegal Celtic were forced to pull out of a game versus an RUC team following threats and intelligence from security services.

Some Cliftonville fans marked Linfield’s return to Solitude with a banner – CEAD MILE FAILTE (100,000 welcomes) but that did not prevent both sets of fans running through their repertoires of sectarian songs. Some Linfield fans had refused to go to the match because they disagreed with the small allocation and doubtless Cliftonville lost thousands off the gate in what would have been an eagerly anticipated encounter.

The game ended 1-1 which was probably for the best.

The situation has improved since that return to Solitude with the PSNI in 2008 allowing Linfield supporters to travel to North Belfast for their games versus Cliftonville under their own steam. No-one seriously expects there to be a love-in at those fixtures but that is significant progress.

Though it is not perfect. Linfield fans have boycotted the fixture following Cliftonville’s protest at God Save The Queen at an Irish Cup Final and Cliftonville fans were alleged to have vandalised a war memorial in Coleraine at Narrow Water in subsequent years.

Who knows when we will ever play a derby at Sunderland again but for all of the vitriol we experience in that fixture, it will never reach what it got to in Belfast.

Scott Robson